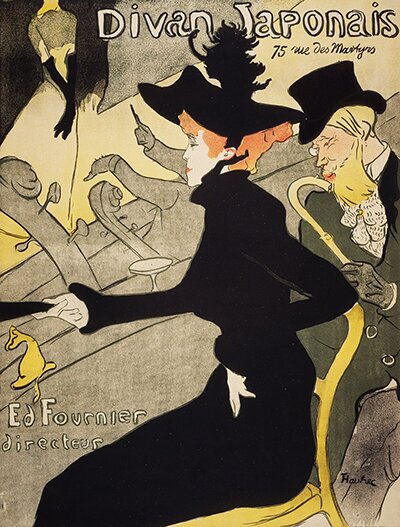

The Divan Japonais was a newly decorated establishment in the Parisian artistic quartier of Montmartre that was re-designed to reflect the Japanese vogue of the time and was epitomised by the use of bamboo and lanterns. The Divan’s owner Edouard Fournier commissioned the piece to promote his establishment at 75 Rue De Martyrs. These details appear on the poster as does Lautrec’s signature. The Divan was one of the many establishments frequented by Lautrec during the Belle Epoque. The small restaurants in the area were his haunts and those of his confreres Degas, Manet, Detaille and Boldini etc. On a typical night they could decadently visit the Moulinde la Galette, Élysée-Montmartre, Divan Japonais, Circus Fernando ending the night at the Chat Noir.

In addition, there are also the well documented visits to Folies Berger, Lapin Agile, Moulin Rouge and the brothels of the area. The poster is an iconic representation of art nouveau chic and style. The image is divided into three diagonal planes and the text is added on the horizontal. The colours used (red, yellow and green) appear flat because of the lithographic process itself. The lines are long, sinuous and organic and there is cropping and asymmetry. This was more to do with Lautrec’s innovation than outside influences.

The three planes are the stage, the orchestra pit and the theatre box. In the background on the stage is a decapitated, lithe and grey singer with long black gloves. This is Yvette Guilbert a chanson realiste performer well known to the audiences of Montmartre and an ex-lover of Lautrec. Guilbert was often disappointed by Lautrec's portraiture of her particularly in the painting Yvette Guilbert Taking a Curtain Call (1894). In designing this poster Lautrec may have deliberately decided to cause offence.

There is a telescopic effect in reverse as the attention moves toward the sinuous lines of the cello's and the conductor in the orchestra pit. Again, the hues are muted. The structure of this piece suggests that the entertainment in these establishments was incidental. The real drama was in who was attending the event. Users of 21st Century social media accounts will no doubt be disappointed that they have merely recycled a 19th century phenomena. Essentially, this lithograph is not advertising a venue – it is smugly promoting a lifestyle.

Centre stage we have the first appearance of Jane Avril in one of Lautrec’s posters. Jane was a favourite dancer of Lautrec. She was hired by the Moulin Rouge in 1889, headlined at the Jardin De Paris and then, because of Lautrec’s posters, exhibited her cancans in London in 1896. The full palette available is used in the theatre box particularly in relation to the red hair of the main attraction who appears to be literally larger than life in scale. Again, the elegant sinuous lines of a body appear to exhibit a nonchalant sexual power. This is accentuated by the curves of the bamboo chair which are themselves reinforced by the walking stick carried by her companion.

The (apparently leering) companion is Édouard Dujardin, an art critic and founder of a journal for fans of Wagner. In his novel Les Lauriers Sont Coupes he developed his own notions of the stream of consciousness which influenced the work of James Joyce in his novel Ulysses. In 1938 Joyce, in further acknowledgement of his literary debt, arranged for the translation and publication in English of Dujardin’s novel named We'll to the woods no more.

How Lautrec depicts his subjects has humanity but it is also tinged with sarcasm. Fans of Lautrec have often declared him as the supremo of the lithograph and the father of advertising. Lautrec himself conferred this honour on the master, Jules Cheret. During the 1890's, lithographed posters proliferated because 'fly-posting' laws were relaxed and Cheret's skills in chromo-lithography led to Montmartre streets being described as art galleries. Contemporaries of Lautrec and Cheret include Alphonse Mucha. Later acolytes include Pablo Picasso, pop artists and advertisers in general.